Por Mariano Fressoli, Patrick Van Zwanenberg y Anabel Marin

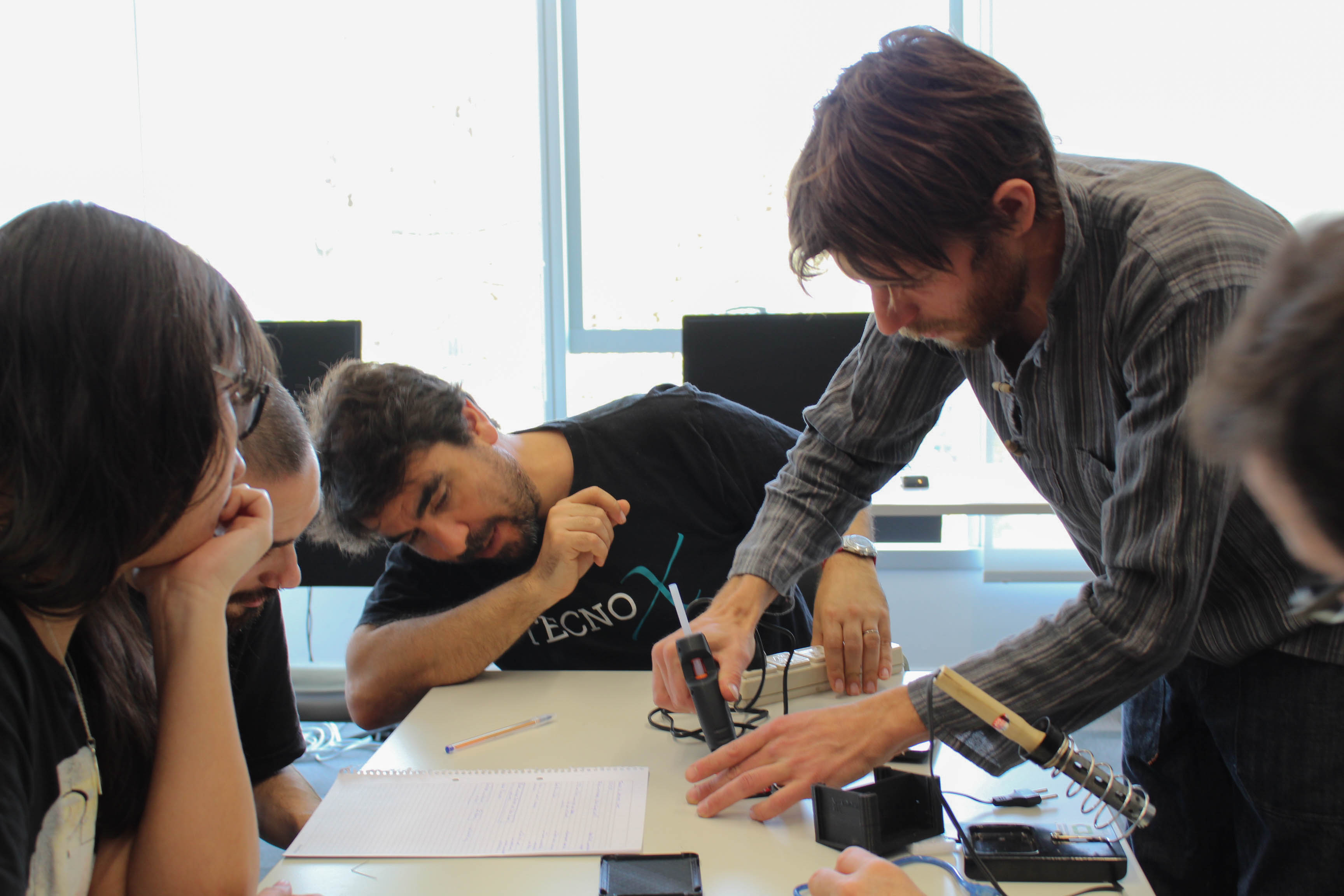

The open hardware workshop was held at the Science Cultural Center in Buenos Aires, as a program of events on open science organized by the Ministry of Science, Technology, and Innovation, Cientópolis, and our institution, Fundación Cenit. Approximately 50 scientists, science teachers, librarians, and hackers participated in an introduction to open hardware for science. Guided by Fernando Castro, an electronic engineer from Mendoza and member of the Open Hardware for Science Group, the group built and tested a small light sensor from a ready-to-use kit. It was a practical way to learn about some of the benefits of open hardware: lower instrument costs, democratization of knowledge, flexibility of use, and the ability to take advantage of a huge library of open source code and designs. As Fernando explained, one of the interesting things about open hardware is that there is already a wealth of open knowledge with which to begin experimenting and building equipment. For small, general-purpose instruments such as microscopes, air monitoring sensors, small robotics, etc., there is no need to reinvent the wheel.

It is possible to use available open data repositories. This is no small thing if you don’t have the resources to purchase what is typically expensive commercial scientific equipment, or if the instruments you need are simply not available on domestic markets. Open hardware provides an opportunity to overcome some of these obstacles, provided you have a minimum level of skills and resources. Although most of the workshop participants were new to open hardware, most possessed that minimum level of skills. Several participants were able to program software and work with electronics, and almost all were aware of the fundamentals and working methods of open source systems. It was easy to present the benefits of open hardware, even though most people had never seen an Arduino open hardware microcontroller before.

Fieldwork, in the field

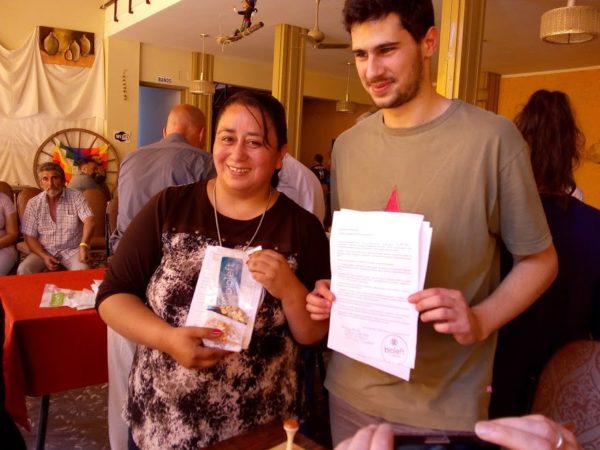

The following day, we traveled to San Pedro de Colalao, a semi-rural area in the province of Tucumán, where we presented Bioleft. We met with representatives of national organizations of small farmers and indigenous peoples, and the idea was to present the project and begin an exchange of seed varieties from breeders to farmers, under an open-source license, for a participatory breeding program. The license, based on the idea of copyleft, ensures that access to germplasm will remain unrestricted in order to improve the reproduction and development of new seed varieties. The license prevents anyone from exclusively appropriating genetic material that is part of communal property protected against biological theft, for example with patents, in a way that restricts the use of that material for further reproduction. At the same time, the idea behind Bioleft is to support a form of peer-to-peer seed reproduction among small farmers and public sector breeders, using a digital platform. If Bioleft is successful, it will eventually present an alternative to the types of seeds that are available in the private sector, which are created for larger commercial forms of production and are, for the most part, unsuitable for small farmers.

As the workshop progressed, some of the challenges of implementing an open source license for participatory seed breeding became increasingly apparent. Small farmers were physically and culturally distant from the geek audience that attended the event at the Science Cultural Center in Buenos Aires the day before. Most were unfamiliar with open source practices, such as the notion of viral copyleft licensing, and did not have much experience with digital social networks. Small farmers generally have a cell phone and use WhatsApp, when they can get an Internet connection, but rarely use email. The practical difficulties of trying to get small farmers, scattered throughout the country, to work together with seed breeders from distant universities via a virtual web platform, rather than through face-to-face contact, even with the help of local extension workers, are quite substantial.

And yet, the ideals and practices of sharing embodied knowledge among smallholder farming communities and open source communities are very similar. Sharing seeds as a way to disseminate, improve, and adapt tools is, in theory, quite similar to the reasons for sharing software code or scientific knowledge. Farmers share their artifacts under reciprocal agreements, hoping to access different types of seeds and improve genetic stock, and they have their own networks, seed fairs, and a long tradition of doing so. But this is a very different world. The language, technical requirements, and practices are totally different between the digital world of open source and that of traditional seed sharing.

For example, while the use of copyleft-like open source licenses is well known among hackers and scientists, it is a rather strange idea among farmers. Our audience was well aware that traditional “open commons” of seeds were under threat, and that companies could appropriate seed material that had been developed by farming communities for hundreds of years. But the idea first proposed by the free software movement, of using intellectual property rights to enforce sharing and protect against exclusive appropriation, was unfamiliar. Furthermore, for small farmers and indigenous leaders, the idea of signing a contract can be confused with a commercial transaction or dealing with a private company. When we tried to explain how Bioleft’s open license works, the first instinct of several people in our audience was the fear of being deceived by a malicious company. The idea that open licenses could protect openness and sharing was also highly questioned. If seeds were open for everyone to use, what would prevent companies from appropriating the knowledge built into the seeds? What would be the benefit of sharing knowledge with people or institutions that do not share the same ideals?

There is a significant gap between practice and language, from open hardware for science to open seeds. These differences point to the need to focus not only on developing technical tools and capabilities, but also on communication and trust. It took some time to explain the details of Bioleft, and it will inevitably require more meetings and the development of new, more educational tools to describe how the Bioleft license idea works, and to modify and implement a web platform for participatory breeding. This communication process must be genuinely reciprocal, so that farmers’ ideas, practices, and metaphors about exchange and common ownership are articulated with those that emerged in digital cultures.

Moving from the idea of protected commons to protected seed commons will require addressing a new set of challenges, including communication, commitment, infrastructure, and strategy. These challenges are substantial, but so is the need to transcend and expand the niche of new digital commons to encompass more traditional practices. To make progress in rural settings, more than viral spread will need to be encouraged. As with seed production and cultivation, transformations take time and care